Gardens And Grounds – How To Creatively Conserve The Gardens Around A Listed Property

Landscape Architect and Specialist in Historic Garden Conservation Marian Boswall, shares her studio’s approach to creatively conserving the gardens and landscape setting around a listed property.

A garden is an investment

Like an old master painting, a garden should make you happy every time you look at it, but unlike a work of art a garden is constantly changing and can fall into disrepair if neglected. You may inherit a garden so overgrown or neglected that you almost have to start again, so where do you begin?

If you buy a listed building it has certain elements which cannot be changed without permission, and a listed garden is the same. The grounds within the curtilage of a listed property have certain protections and constraints, so how can you work within those planning and listed building constraints to create something that enhances the setting, that contributes to your enjoyment of the house and that will endure as part of your legacy?

Wait a year

When you first buy a listed property the garden may be some way down a long list of maintenance and repairs that need your immediate attention And this can be no bad thing, as the best advice can be to wait a year and take time to really observe what you have inherited in the garden.

Take stock

In a large garden it is a good idea to get a survey done by a professional company or use the deeds or ordnance survey map to create a base plan, whilst in a smaller garden you could pace it out yourself. On this you can mark North, note where the sunny spots are through the day in each season and which mature trees cast welcome shade or are sick or overgrown and in need of help.

In Spring and autumn mark where bulbs have been lovingly hidden by past owners to surprise you, and where bind weed, ground elder or suckering shrubs have got the upper hand. Note the services and drains, any overhead wires, the prevailing wind and sources of noise or smell, both good and bad. Are there damp areas by the house or puddles in paths, lawns that lay wet or ponds that dry out? These can all be rectified in time and we’ll look at how in this series. See how you use the garden and what is missing.

Take stock of where there are good views out of the garden, or anything ugly you’d prefer to screen, plus the most beautiful parts of the garden to celebrate, and the main views from important windows, especially above the kitchen sink!

Research the history

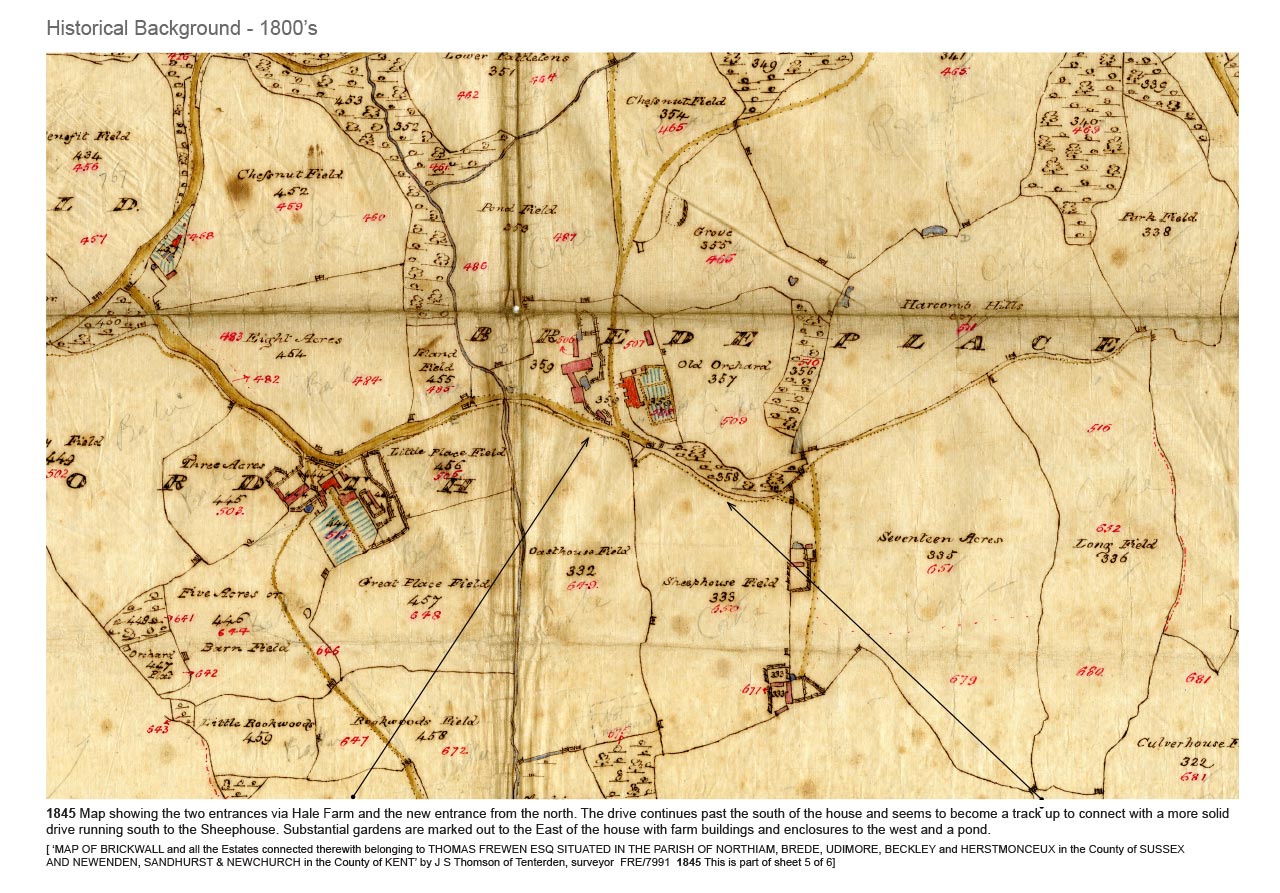

Old plans and photos are a great resource to understand how the garden has developed over time. Your predecessors may have photos or your local archives may have a wealth of old maps and plans and snippets of local history. These are free to access but you may have to order items on line before turning up, or face a wait. To search the online catalogue see http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk. You may even strike gold and discover old paintings or writings by previous owners.

At Charleston we were able to use the Bloomsbury Set’s art as inspiration to explore the textures and forms of the landscape and so ensure continuity of the Spirit of Place. One day I hope to see the mighty Elms behind the barn replanted to tower up against the Firle again as they do in Duncan Grant’s paintings.

Know your period

If there are no records of the history of the garden you can refer to similar period gardens to know what would be appropriate for your site. National Trust properties are great for this, as are the Country Life Archives. It’s important to design the hard landscaping to be in keeping with the house, and the planting style should be sympathetic, but does not need to be constrained only to plants available at the chosen period. When designing planting around a contemporary extension for example it can be fun to vary the style of planting as well.

Understand the setting

Understanding the setting is important and so is the underlying geology, soil type, microclimate and existing flora and fauna. In a town there may be a Conservation Area Appraisal which will have guidance and in the countryside the NPPF describes the character areas for each AONB which can help with understanding the local vernacular and typical layout of hamlets and farmsteads. Looking at local brickwork, gates and neighbouring properties can help as well.

Start with structure

When you are planning the design start with the structure: trees, hedges, walls and shrubs will define the space and can be filled in later with herbaceous planting if you cannot do it all at once. A concept masterplan can really help to articulate the whole vision for the setting and allow you to develop areas over seasons or years as time and budget allows. Once you are ready to implement your design ideas you should check whether permissions are required and an informal chat with you local conservation officer can be a good place to start.

Significance

If you are planning major changes to the garden levels, layout or structures within the curtilage you may need listed buildings consent and planning permission. It will be helpful to have a Statement of Significance which describes the importance of the garden in terms of its historic, aesthetic and community value and explains how your proposed changes respect or add to that significance. Your landscape architect or planning consultant will prepare this and the NPPF is helpful in describing what you should include.

Permission

If you are in a Conservation Area or there are TPOs on your trees you will need permission before carrying out any work on them. An ecology survey may be needed as part of a planning application if you wish to remove old features and you may need licenses for dormice, newts or bats if they are present, and to put in special measures to mitigate for any habitat loss. An Archaeology survey may be needed for an historically important site, and you may need a watching brief from an archaeologist if you are doing any groundworks.

Image © Zoë Helene Kindermann

Take the long view

Having taken these things into consideration it’s important to plan for the next 50 to 100 years and your designer should illustrate the projected growth of the planting they suggest to make sure it will grow up harmoniously. This is particularly important if you plan to renovate ancient features such as woodlands or avenues of trees.

Plan for maintenance

Finally it’s good to know how much maintenance your garden received historically and how much you should budget for going forward to ensure you can keep it up long term without it becoming a burden. Once the garden is built and planted your designer should hand over with a clear maintenance plan with tasks by season for each area.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

Do I need permission to erect a greenhouse or shed?

Onerous as it may seem, if the greenhouse or shed is proposed within the curtilage of your listed building you will require planning permission, whatever its size. In the rare case where it is attached to the listed building or to a curtilage listed structure you will also require listed building consent.

How do I go about changing the fencing and gates of a listed property?

Some fences, walls and gates which fall within the curtilage of a listed building and were built before 1948 are treated as part of the listed building. So are walls, fences or gates which are attached to the listed building. In these circumstances you will need listed building consent to make any alterations.

Erecting a fence or wall which falls within the curtilage of a listed building also requires planning permission, whatever its height.

No permission is required to plant, maintain or alter a hedge.

Are trees protected near a listed building?

Trees are not given any formal protection by listing which only protects buildings and structures. However, all trees in Conservation Areas are protected and some trees are protected by Tree Preservation Order. If in doubt it is worth checking with the local planning authority before carrying out any work to a tree. Alternatively, your tree surgeon will be very familiar with how to carry out the necessary checks.

USEFUL RESOURCES

Conservation Principles, Policies and Guidance

historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/conservation-principles-sustainable-management-historic-environment/

Conservation Area Designation, Appraisal and Management

historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/conservation-area-appraisal-designation-management-advice-note-1/

Local Archives

www.gov.uk/search-local-archives

Tree Consents

www.historicengland.org.uk/advice/planning/consents/tree/

Fences, Gates and Garden Walls

www.planningportal.co.uk/permission/common-projects/fences-gates-and-garden-walls/planning-permission

This article first appeared in the Listed Heritage Magazine, May 2018