Water In Our Gardens

Recent flooding in the UK has really made us focus on how we manage our water.

What we do in our gardens can make a real difference. The first thing we can do is to catch it in our soil. A healthy soil will hold up to seven times its weight in water and allow it to slowly filter down to the aquifers. Even heavy clay when it has lots of humus and good texture created by microbes will be spongy and drink up water, allowing us to walk across a garden after rain without losing soil or sinking into a sticky mud bath. A healthy soil is up to 80% air pockets ready to fill with water, whilst a compacted soil may only have 5% space left for water and the nutrients it carries to plant roots, so start with creating a healthy soil full of all the microbes. [If you’d like to know more about soil do come to a workshop or get in touch!}

Catching rainwater wherever we can also avoids watering our gardens with the chlorine and chloramine added to mains water which will kill your vital soil microbes. If you have to use mains water to water your garden leave it to stand in a water butt or watering can for 30 mins to allow chlorine to evaporate, and add a bit of humic acid to the water to mitigate the chloramine, or add a biologically complete compost or biologically complete compost tea to your soil after watering to help replenish those crucial microbes.

Rainwater is easy to harvest from most roofs including sheds and greenhouses, so it’s a no brainer to invest in water butts, or a rainwater harvester if you have a larger garden and a larger budget. Harvesting rainwater also reduces pressure on the water and sewage systems which in many places are struggling to keep up with old infrastructure and increasing populations. Our rivers were dug out to be straight and ‘efficient’ often to service factories and power plants during the industrial revolution. The result is rivers that flow fast and banks that crumble in floods. Part of my studio’s work is focussed on rewiggling those rivers and reinstating old floodplains; if you own a riverbank you can help by planting trees on banks and even allowing fallen trees to stay in situ and create permeable dams to slow the flow.

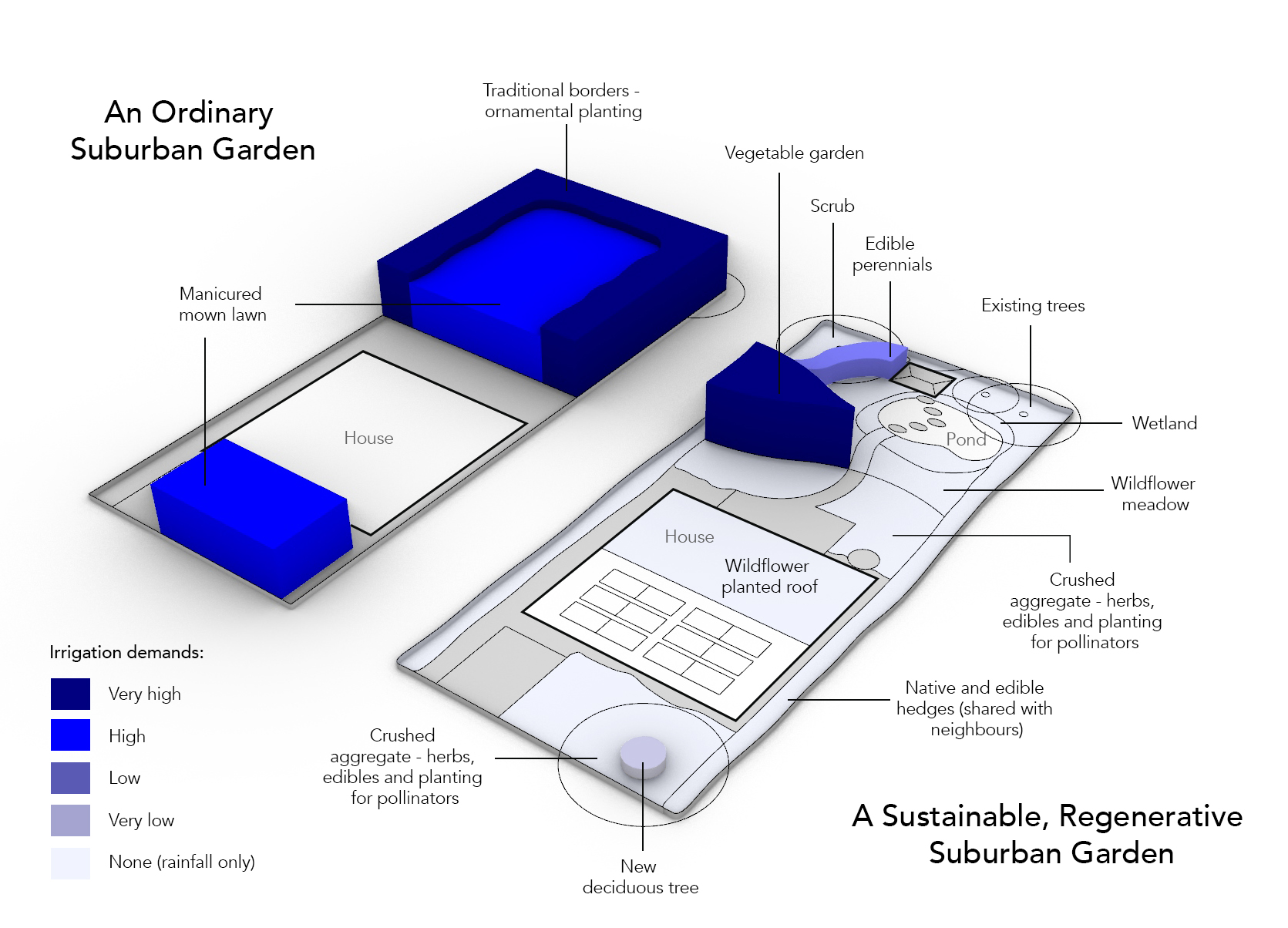

Urban drainage systems were designed to take rain and waste into sewers as fast as possible. Rivers were culverted (put into drains) and front gardens have been paved over for cars. 50% of London is now hardscape (60% of New York City). Whilst we need more sustainable drainage systems and green spaces in our cities, in our own gardens we can create as much green surface as possible to slow down the flow of water and lessen its impact on flooding and nutrient loss. This can include green roofs, planted gravel drives, climbers on walls and bird friendly hedges, or even a fence covered in climbers (edible if possible!)

Once your soil is revitalised water will be asset in your garden. Even a tiny pond, water bath or rain garden will add life to your garden, whilst a shallow dish or bucket of water can be a life saver for small creatures in times of drought. Introducing a pond will revolutionise your ecosystem and improve the microclimate on your land, attracting myriad creatures, retaining water, and emitting cooling mist as it evaporates.

I am often asked how to prevent a pond from going green? The answer is in the biology. The green is algae, a natural occurrence which grows fast in unbalanced ecosystems exacerbated by nitrates and warmth. Shallow domestic ponds with black sun-absorbing liners and few plants are perfect breeding place for bacteria, algae and mosquito larvae, but less good for the creatures that would balance them out. The solution is to ensure some shade, some depth and plenty of varied surface areas for beneficial organisms. You can mimic the rich ecosystem of a shipwreck on a coral reef with different levels, gravel, stones, rocks, bricks and perhaps a sunken structure or two. Float oxygenator plants at the bottom, marginals at the edges and some deep-water lovers. If you are near other ponds, allow nature to bring plants in. The edges of ecosystems are where maximum biodiversity thrives, so wiggle your pond edges to make them longer, add swales and ditches and allow dew ponds and puddles to add to the magic.

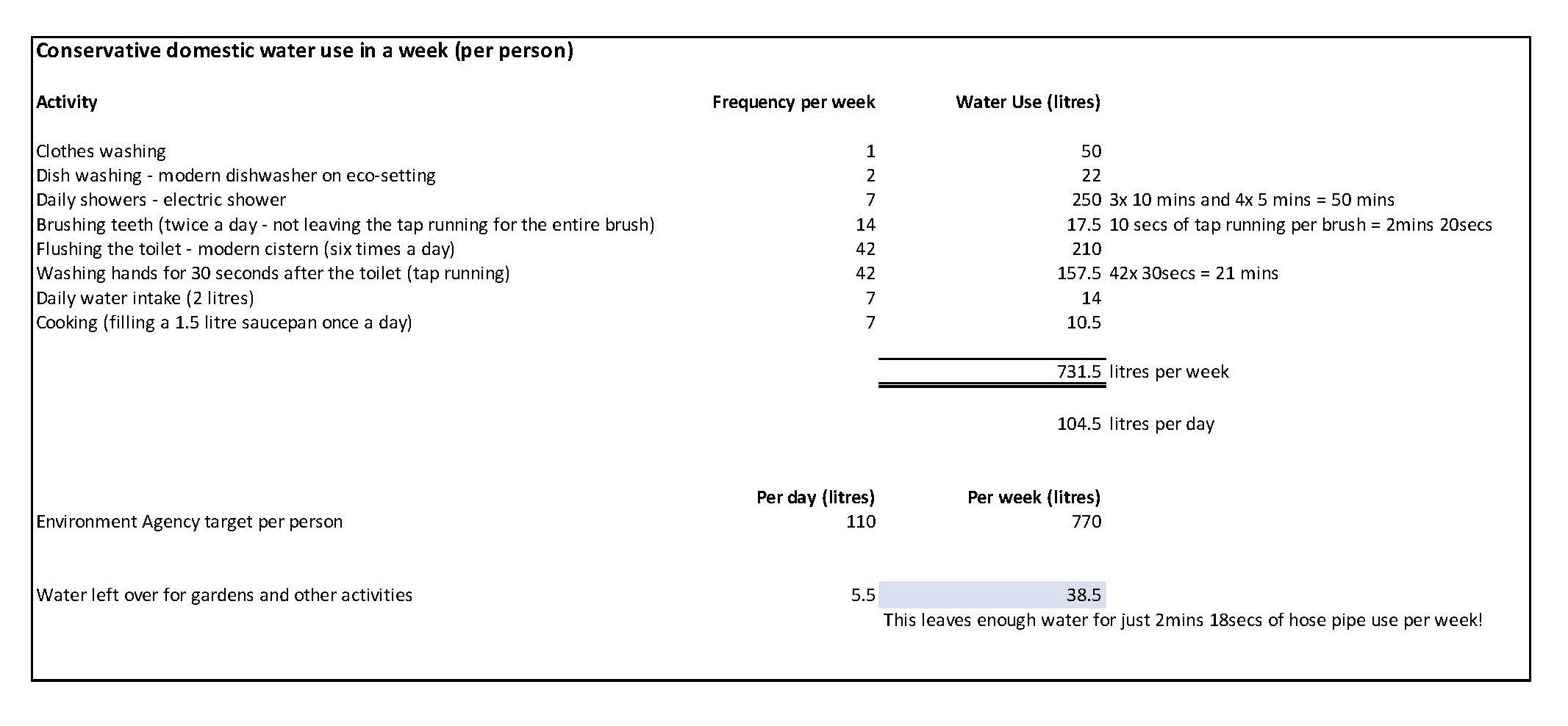

The water-use chart below shows how much mains water is left for irrigation after a ‘normal’ usage of water in a week, if we are to stick to the aim of 110 litres per person per day in the UK. To reduce water usage plant for local conditions, create shade, cover the soil with resilient plants, feed your soil with microbes and mulch. Allow a dew pond to form in a wet spot, or plant water-thirsty willow to coppice for woodchip and weaving. Transition from a labour and water-intensive annual vegetable garden to a permaculture garden, where plants are mostly perennial and grow in self-supporting layers with some annuals between, soil is covered and soil microbes and mycorrhizal networks kept intact.

If you’re planting new trees, start as small as possible, mulch with woodchip or wool and use an irrigation bag to establish larger rootballs. What you plant makes a huge difference too. See the blue diagram above to compare the water requirements of different types of planting. If space is limited opt for plants which can thrive without watering, avoid planting in pots or only use harvested water to irrigate.